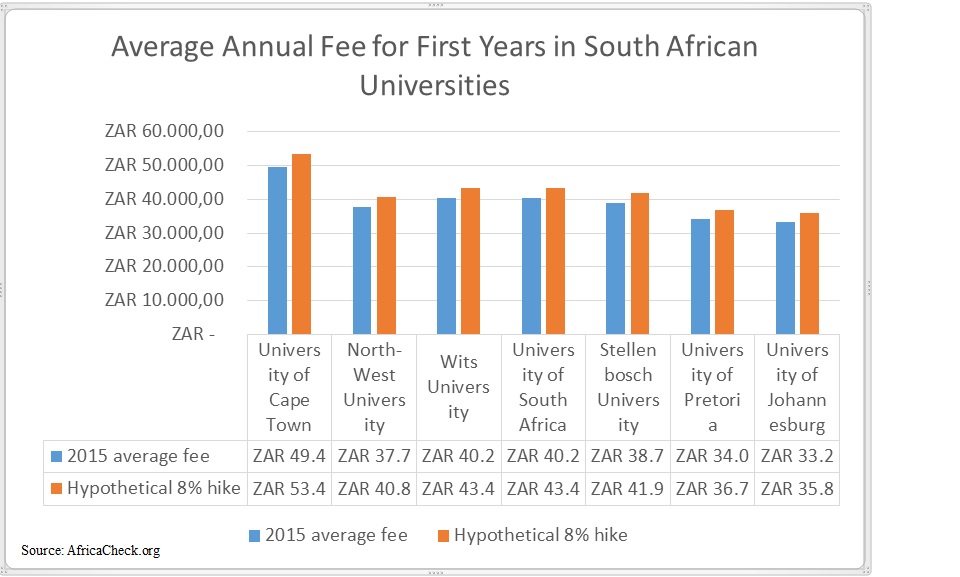

Protests in South Africa have turned violent after the South African Department of Higher Education and Training (DHET) allowed universities to increase fees up to 8%. Activists since been demanding free education through their social media campaign #FeesMustFall. As part of their riot control measures, the police have resorted to rubber bullets and stun grenades, which has resulted in injured students and several arrests. To date, there has been one fatal incident , albeit of a bystander. A janitorial employee at the University of the Witwatersrand, also known as Wits University, was on site when protesters released fire extinguishers, and the ensuing complications ultimately led to his death[1]. These social demonstrations come after a one-year moratorium on tuition fee increases. However, this year, the administration is convinced that universities are in need of resources.

In order to appease protesters, the DHET committed to support children from poor, working and middle class households with an annual income of up to 600,000 rand (US$40,000). Therefore, all National Student Financial Aid Scheme (NSFAS) qualifying students and those in the “missing middle”- individuals that are not poor enough to be eligible for a grant but not rich enough to afford university- will not experience a fee increase. According to official statements, the government pledged to pay for the fee adjustment[2].

The majority of universities remain closed as the protests have disrupted classes and final exams. If the situation continues, some universities could decide to cancel the academic year. The University of Cape Town has already voiced this concern. As of October 8th, it still plans to finish the academic year. Meanwhile, Wits University conducted a poll directed at students and staff. Preliminary results show that 77% of students want to resume the academic program while the remaining 23% prefer the opposite[3].

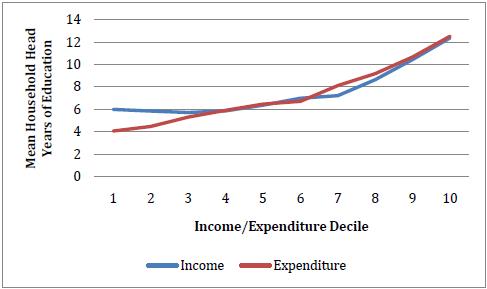

The situation has revitalized the debate on whether it is sensible to demand free education. Students have voiced their ideas on how to obtain funding for this endeavor (found here). Yet, they fail to analyze other factors. Certainly, tuition fees represent a significant financial barrier but there could be other equally, if not more, important factors at play. That is, inequality. South Africa remains one the most unequal societies in the world with an estimated Gini coefficient of 0.65 in 2011[4].

Students coming from households in advantageous socioeconomic environments normally receive better educational opportunities. The National Income Dynamics Study (NIDS) based on a longitudinal survey shows that 31.5% of students that do not finish grade 12 cite lack of money, and their desire to look for a job as the main reasons for dropping out. Most of them are unemployed[5]. Similarly, data collected between 2000 and 2006, show that only 27% of students enrolled in contact institutions graduate within the intended time. An abysmal 45% never graduates. The numbers are even worse for distance institutions[6].

Furthermore, it is almost assured that children coming from poorer households receive lower quality primary and secondary education, hampering their enrolment and chances of success in universities or vocational colleges. Under the current paradigm, schools are assigned a quintile ranking based on their neighborhood’s socioeconomic characteristics and obtain non-personnel expenditure budgets, such that, lower quintile schools receive a larger allocation per learner[7]. This implies that no-fee schools are at disadvantage when it comes to recruiting better teachers vis-à-vis fee-paying schools.

The failure of the education system to maintain students and provide them with the skills necessary to succeed in post-schooling undertakings leads to skill mismatches that ensure high returns to the skilled and low returns for the unskilled, especially in a capital-intensive economy where technological advances increase demand for knowledgeable workers. South Africa has the highest private returns to tertiary education in the world[8]. The rate of return in 2011 was estimated to be, on average, 39.5%[9].

Source: Finn, A., Murray, L. and Woolard, I. (2009).

Income & Expenditure Inequality: Analysis of the NIDS Wave 1 Dataset.

This is not to say that funding is not important. Multivariate analysis conducted by the NIDS show that credit constraints are significant in explaining enrolment in universities and Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TVET) colleges[10]. Still, free education would disproportionately benefit the wealthy. The average household income for students enrolled in university is three times that of individuals who do not enroll in post-secondary education or attend TVETs. It is nonsensical for the average household to pay for the education of the rich through higher taxation. Students coming from lower quintile schools are likely to be excluded from free higher education as their dropout rates are higher[11], thus, they do not meet the requirements or lack sufficient knowledge to enroll in university or vocational training. In fact, approximately half of the students in South Africa do not complete matric[12].

Additionally, experts have argued that free education is not financially possible for a developing economy as opposed to developed ones[13]. Norway, a country that enjoys high employment rates and decent wages, finances free education and other services through very high taxation. Indeed, funding requires improvement, but systemic issues must first be addressed. Inefficiencies in the undergraduate system -high retention rates and low graduation rates- create economic pressures for institutions and undermine the NSFAS. From February 2015 to February 2016, tertiary education inflation was at 9.8% while overall inflation stood at 7.0%[14]. Most of the NSFAS recipients that are no longer studying dropped out or did not finish[15]. An official report shows that no institution was able to cover full cost of study using NSFAS funding. These are students that are now burdened with debts they cannot afford as their employment opportunities are very limited.

Structural reforms that improve schooling, especially, during secondary years would be more effective. South Africa must strive for higher completion rates and improved teaching quality for historically disadvantaged communities so as to increase their probabilities of success in post-secondary education. For African and coloured youth (official census data), it is less than 5%[16]. Otherwise, free education will only widen inequalities, as the rich will be better-equipped to compete for access in universities that will have to be selective.

[1] University of the Witwatersrand Statement. (2016). Condolences from Wits University. University of the Witwatersrand. https://www.wits.ac.za/news/latest-news/general-news/2016/feesmustfall2016/statements/condolences-from-wits-university.html

[2] DHET News. (2016). 2017 Fee Support Announcement: Infographics. Department of Higher Education and Training. http://www.dhetnews.co.za/2017-fee-support-announcement-infographics/

[3] University of the Witwatersrand Statement. (2016). #Witspoll: Majority of Students Support Going Back To Class On Monday. https://www.wits.ac.za/news/latest-news/general-news/2016/feesmustfall2016/statements/witspoll-majority-of-students-support-going-back-to-class-on-monday.html

[4] International Monetary Fund. (2016). IMF Country Report No. 16/217. International Monetary Fund. https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/scr/2016/cr16217.pdf

[5] Branson, N., Kekana, D. and Lam D. (2013). Educational Expenditure in South Africa: Evidence from the National Income Dynamics Study. NIDS. http://www.nids.uct.ac.za/publications/discussion-papers/wave-3-papers/185-educational-expenditure/file

[6] Cloete, N. (2016). Free Higher Education: Another Self-Destructive South African Policy. Centre for Higher Education Trust. http://www.chet.org.za/files/Higher%20education%20and%20Self%20destructive%20policies%2030%20Jan%2016.pdf

[7] Branson, N., Kekana, D. and Lam D. (2013). Educational Expenditure in South Africa: Evidence from the National Income Dynamics Study. NIDS. http://www.nids.uct.ac.za/publications/discussion-papers/wave-3-papers/185-educational-expenditure/file

[8] Montenegro, C.E. and Patrinos, H.A. (2014). Human Development Reports Comparable Estimates of Returns to Schooling Around the World. The World Bank.

[9] [9] Cloete, N. (2016). Free Higher Education: Another Self-Destructive South African Policy. Centre for Higher Education Trust.

[10] Branson, N. and Khan, A. (2016). The Post-Matriculation Enrolment Decision: Do Public Colleges Provide Students with A Viable Alternative? Evidence from the First Four Waves of the National Income Study. NIDS. http://www.nids.uct.ac.za/images/papers/2016_09_NIDSW4.pdf

[11] Branson, N., Lam, D. and Zuze, L. (2012). Education: Analysis of the NIDS Wave 1 and 2 Datasets. NIDS. http://www.nids.uct.ac.za/publications/discussion-papers/wave-2-papers/131-education/file

[12] Branson, N. and Khan, A. (2016). The Post-Matriculation Enrolment Decision: Do Public Colleges Provide Students with A Viable Alternative? Evidence from the First Four Waves of the National Income Study. NIDS. http://www.nids.uct.ac.za/images/papers/2016_09_NIDSW4.pdf

[13] Council on Higher Education. (2016). Kagisano 10. http://www.che.ac.za/sites/default/files/publications/Kagisano%20Number%2010%20-%20Student%20Funding%202016%20-%20electronic.pdf

[14] Statistics South Africa. (2016). Consumer Price Index. http://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/P0141/P0141February2016.pdf

[15] Cloete, N. (2016). Free Higher Education: Another Self-Destructive South African Policy. Centre for Higher Education Trust. http://www.chet.org.za/files/Higher%20education%20and%20Self%20destructive%20policies%2030%20Jan%2016.pdf

[16] Council on Higher Education. (2013). A Proposal for Undergraduate Curriculum Reform in South Africa: The Case for A Flexible Curriculum Structure. http://www.che.ac.za/sites/default/files/publications/Full_Report.pdf