This article was originally published at globaldev by NCID Resident Fellow Tijan Bah, together with his co-researchers David McKenzie, Catia Batista and Florence Gubert. You can read the original article here. This piece refers to the project Information Gaps and Irregular Migration.

Given the vast income differences between Africa and Europe, there are powerful incentives for migration even by irregular, costly, and potentially dangerous means. But has Covid-19 changed young people’s plans? This column reports from the Gambia that the pandemic has reduced the intention to migrate via ‘the backway’ to Europe for poorer and less certain youth. However, the overall desire to migrate remains very strong, highlighting the need for safe legal pathways.

Expanding youth populations, lack of economic opportunity, political instability, and conflict have all contributed to the growth of irregular migration from Africa to Europe over the last decade. Almost a million sub-Saharan African migrantsapplied for asylum in Europe between 2010 and 2017.

But legal pathways for migration are limited – and so the most common way for young people to migrate from West Africa to Europe is through what is referred to as the ‘backway’. This describes an overland journey through West Africa, across the Sahara desert, and into Libya, from where youth attempt to catch boats to Italy and other European destinations, with each stage involving multiple risks.

Images of young African men on crowded rubber boats put the phenomenon under the political spotlight, as well as raising attention to the humanitarian costs to the migrants who face risks of abuse and loss of life on these journeys.

In response, the European Commission set up a €4.8 billion Emergency Trust Fund for Africa to support migration- and displacement-related programming designed to reduce the incentives for people to migrate. But migration experts notethat past experience suggests the capacity of development assistance to deter migration is small at best.

One reason for this is that the income gaps between countries are so large. For example, income per capita in 2019 was $778 in the Gambia, and 42 times as high in Italy at $33,228. Faced with these vast differences, it comes to no surprise that 56% of the 3,700 young Gambian people whom we interviewed in 2019 said that they would migrate to Europe if they had the opportunity.

The Gambia has a long history of migration, in part due to its small size and geographical location on historic trade routes. Migration to Europe and asylum-seeking increased following a coup in 1994, leading to the Gambia becoming the African country with the highest incidence of irregular migration relative to its total population, according to 2017 data. The remittances sent by this diaspora constituted 20% of Gambian GDP, helping to support many families.

How did the pandemic change this intention to migrate?

Covid-19 acted to limit legal opportunities for migration further as borders closed, leading to suggestions that irregular migration could increase further in response. But the pandemic also affected other considerations in the migration decision, making the overall impact theoretically unclear.

On the one hand, worsening economic conditions at home and potentially fewer remittances from abroad could spur more people to try to leave. On the other hand, lower income at home means less ability to finance the costs of migration. What’s more, the health impacts of the pandemic were more severe in the main European destinations than in the Gambia; and earnings opportunities in the main destinations fell.

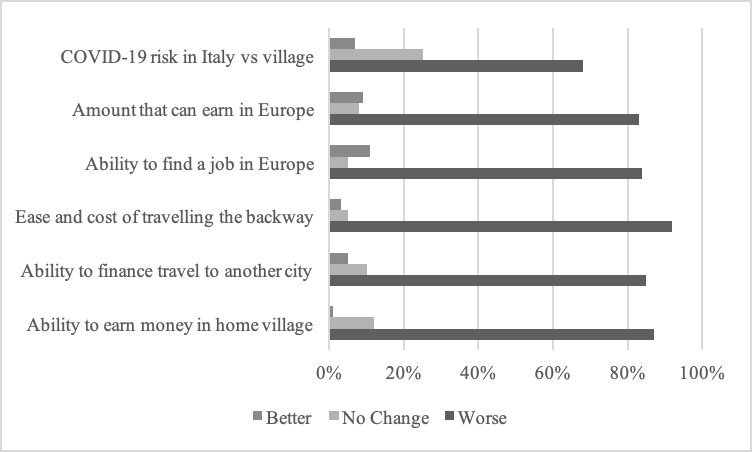

Figure 1 illustrates how these different migration ‘push’ and ‘pull’ factors worsened for almost everyone in our sample.

Figure 1: Changes in migration push and pull factors

In our recent research, we re-interviewed Gambian men aged 18 to 33 between September and October 2020 to see whether the pandemic had changed their intentions to migrate to Europe, and also to a nearer migration destination – Dakar, the capital city of neighboring Senegal.

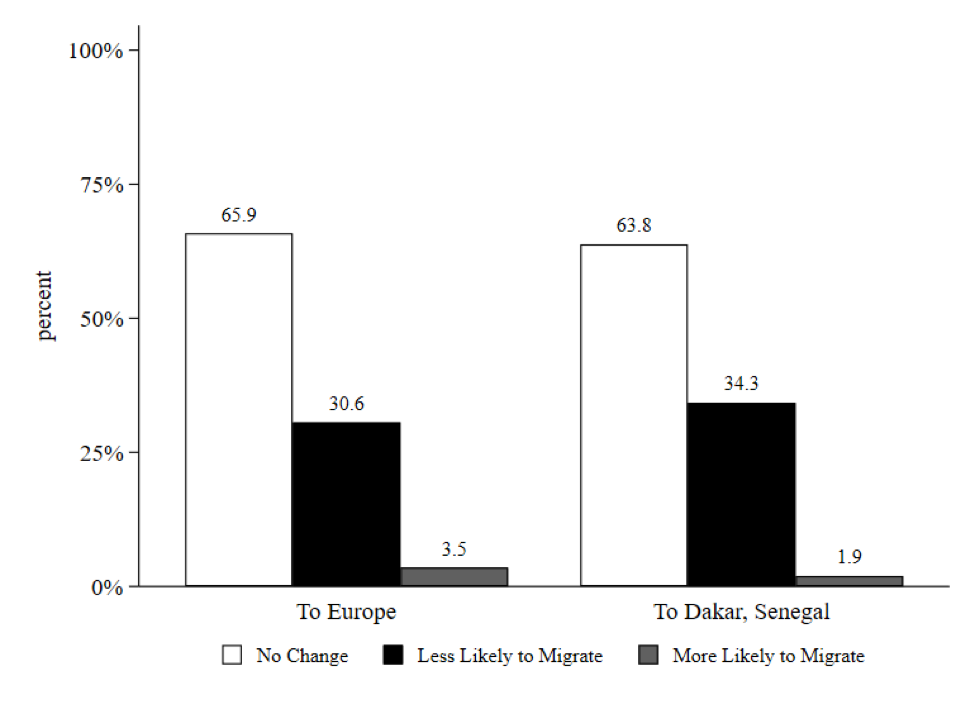

Figure 2 summarizes the first key result: two-thirds of respondents say they have not changed the likelihood of wanting to migrate to Europe, 30.6% say they have become less likely to want to migrate, and only 3.5% have become more likely to migrate. The changes in intentions are similar for the intention to migrate to Dakar.

Figure 2: Reported effect of Covid-19 on intention to migrate to Europe and to Dakar

We experimentally varied how salient the pandemic was when people were answering this question by randomizing whether an information video and a series of questions about the pandemic’s effects on them were asked before or after these migration questions, and find responses are similar in both cases. We attribute this to the pandemic already being very much at the top-of-mind when considering migration decisions.

We then examine which youth are most likely to be among the 31% who say they have become less likely to migrate. Youth who were uncertain about whether they wanted to migrate before the pandemic are the most likely to have changed their minds away from migration, as are poorer youth who can no longer afford the costs of the backway journey.

The desire to migrate remains incredibly high

The pandemic has therefore done what almost €5 billion in aid was less successful in achieving, which is to reduce the desire to migrate from Africa to Europe. But it is unclear whether this reduction in intentions is permanent, or whether the intent to migrate will increase again once the pandemic is over.

Moreover, despite this reduction in intentions to migrate, the desire to migrate to Europe remains incredibly high among these young men, with 65% saying they are likely or very likely to try to migrate, and 58% saying that they would consider the backway.

This raises several potential areas for policy action. The first is to explore policy options to open more legal avenues for migration to Europe, given this high demand.

The second, which we are currently testing in a randomized experiment, is to experiment with different approaches to reducing the demand to migrate irregularly.

One way to do this is by working with returnees to provide more information about the dangers and risks of the journey; a second is to provide youth with support to migrate to closer and safer destinations such as Dakar; and a third is to provide more opportunities at home through vocational skills training.