It is estimated that 11 million Syrians have fled their country since the beginning of the civil war in March 2011. Amongst those escaping their homes, the vast majority have sought refuge in neighbouring countries –4.9 million according to UNHCR[i]– while 1 million have requested asylum to Europe, creating a humanitarian crisis that has sown of refugee camps many countries.

However, in Kenya, refugee camps are neither rare nor provisional (Hyndman et al.[ii]). Refugee camps are not meant to be permanent, but for decades Kenya has hosted, among others, the world’s largest refugee camp, Dadaab, hosting nearly 261,500[iii] Somali refugees –which accounts to roughly 78% of the 334,200[iv] registered refugees in the whole country–, a figure that rises to as many as 600,000 people when itinerant families and individuals are included. Set up in 1991 by the UNHCR, it has existed in a complicated equilibrium between the UN and the Kenyan government since its inception.

Last May, the Kenyan government announced it would shut down the refugee camp of Dadaab. And, as with other cases around the world, when rejecting refugees, the government is citing national security interests. That means many of the Somali refugees in the camp will eventually be sent back Somalia.

Tensions have been rising and there has a debate for quite some time between the United Nations and Kenya. The UN has warned the host country that prematurely and illegally closing Dadaab could have devastating consequences.

To this date, Kenya has agreed that the repatriation of Dadaab residents will be voluntary, safe and dignified. That is stated in international law and it was also repeated by Valentin Tapsoba, director of UNHCR’s Africa Bureau: “UNHCR is committed to ensuring that all returns to Somalia are voluntary and carried out in dignity, safety and with the protection of refugees paramount at all times”.[v]

The non-refoulement principle is enshrined within the 2013 tripartite agreement on Voluntary Repatriation of Somali Refugees Living in Kenya signed in November, 2013 between the UN, Kenya and Somalia. And equally important is the 1969 African Refugee Convention, of which Kenya is a state party. For that reason, moving hundreds of thousands of refugees back into Somalia is complicated. There, Al-Shabab still poses a huge threat. Even though terrorist have been weakened by international and Somali forces, the group still has a strong presence in rural parts of Somalia, particularly in the south. As a result, without refugees’ cooperation, repatriation is not only difficult, but also illegal, being breach of international and Kenyan law.

National Security at stake

There are many studies on host state and refugee’s security dynamics –a good example is the paper on The Dilemma of Hosting Refugees (Kirui et al.[vi]) which focuses precisely on Dadaab refugee camps in Northeastern Kenya–.

The position held by Kenya on the situation of Dadaab is that it is a hub for terrorist recruitment. Kenyan officials state that Al-Shabab –Al-Qaeda affiliate in Somalia– has been using refugee camps in Kenya to do recruitment. That was the position of Joseph Kkaissery, Interior Cabinet Secretary, who stated in May 11th that “Kenya cannot look aside and allow this threat to escalate further” …“There comes a time when we must think primarily about the security of our people.… That time is now.” [vii]

The UN has criticised such statements and accused the Kenyan government of using refugees as scapegoats to win votes in next year’s national elections –scheduled to take place in August, 2017– as well as claiming that Kenya is subverting international law.

However, after negotiations, the UN, Kenya and Somalia said in a joint statement on June 25th that they had agreed on a timeline which aims to reduce Dadaab’s population by 150,000 by the end of 2016. Due to previous statements from the Kenyan government and UNHCR schemes, between December 2014 and the end of September 2016, 30,731 Somali refugees from Dadaab have been repatriated. However, 24,630 of them have returned to Somalia in 2016, because of pressure from the Kenyan government to clear Dadaab. Furthermore, over the past few months, since the announcement last May to initiate the closure of Dadaab, there are 400 people being transported every day across the border into Somalia[viii].

When money leads the way

Kenya’s final decision to shut down Dadaab came a couple of months after the European Union signed a 6 billion euro agreement with Turkey in March to reduce the flow of refugees going to Europe. That has given Kenyan officials a certain bargaining power with the UN, which appears to be following Turkey’s lead. Kenya seems to be telling the UN to either pay and contain the situation yourself, or leave.

All efforts are currently being put on the Syrian refugee crisis and the shift in donors’ attention to Europe is clear. Because of this situation, Karanja Kibicho, Kenyan Principal Secretary of the Interior –which includes national security- said that “international obligations in Africa should not be done on the cheap”[ix], clearly stating that the more international donor money goes to the European refugee crisis, the greater is the drop in international funding for the camps in Kenya.

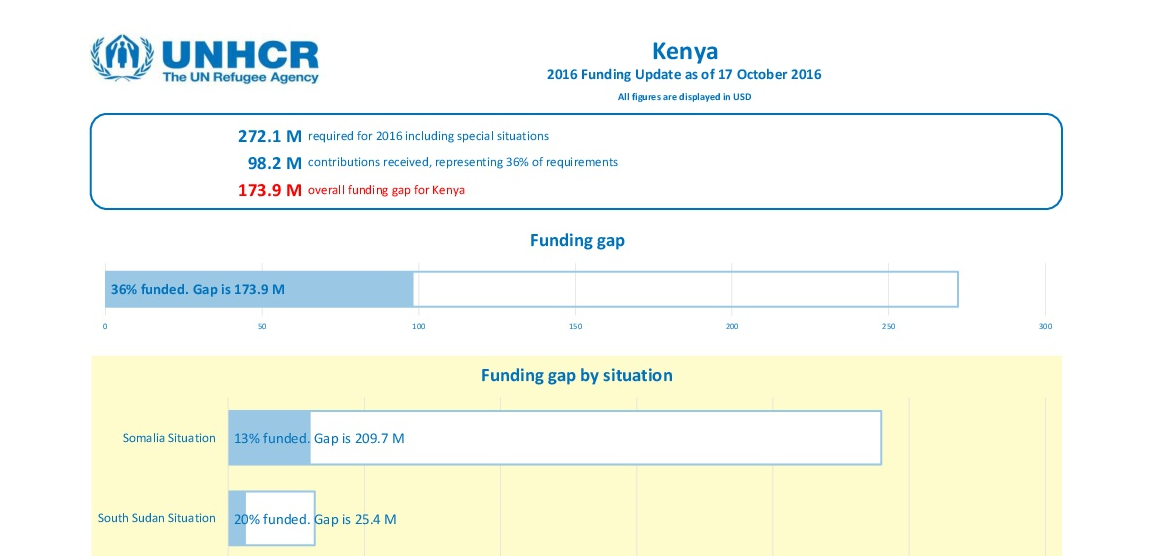

And this is a legitimate concern. According to Andreas Needham, a UNHCR spokesman, UNHCR’s programs have about half the funding they need, but the shortfall in African countries is much greater. Only in Kenya the UNHCR is in need of USD 272.1 million of which only 36% of it is already funded. And with respect to different situations affecting Kenya, the gap in the Somalia situation is even larger –only 13% has been funded and USD 209.7 million are yet to be seen. [x]

[i] UNHCR appeals for additional $115 million for voluntary return, reintegration of Somali refugees from Dadaab camp (26 July 2016) http://www.unhcr.org/news/press/2016/7/5797585c4/unhcr-appeals-additional-115-million-voluntary-return-reintegration-somali.html

[ii] Kirui, P. and Mwaruvie, J. The Dilemma of Hosting Refugees: A Focus on the Insecurity in North-Eastern Kenya (2012). International Journal of Business and Social Science.

http://www.ijbssnet.com/journals/Vol_3_No_8_Special_Issue_April_2012/18.pdf

[iii] Government statement and update on the repatriation of refugees of Dadaab Refugee Camp (2016) http://www.interior.go.ke/?p=3113

[iv] The UN is sending thousands of refugees back into a war zone. September 26, 2016. http://foreignpolicy.com/2016/09/26/the-u-n-is-sending-thousands-of-refugees-back-into-a-war-zone-somalia-kenya-dadaab/

[v] Securing Kenya (2016) http://www.interior.go.ke/?p=3107

[vi] United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) http://www.unhcr.org/figures-at-a-glance.html

[vii] Hyndman, J. and Nylund B. (1998). UNHCR and the Status of Prima Facie Refugees in Kenya. Oxford Journals

http://www.yorku.ca/jhyndman/pdf/InternationalJournalRefugeeLaw-98.pdf

[ix] Kenya Registered refugees and asylum-seekers. 30 April 2016. UNHCR https://data.unhcr.org/horn-of-africa/download.php?id=1862

[x] UNHCR Kenya 2016 Funding Update as of 17 October 2016. http://reporting.unhcr.org/sites/default/files/Kenya%20Funding%20Update%2017%20October%202016.pdf